Beto Borges, Director of Forest Trends’ Communities and Territorial Governance Initiative talks with Céline Cousteau, humanitarian, environmental activist, filmmaker, and founder of the Javari Project for a conversation on her work with indigenous communities in Brazil.

This conversation has been edited and condensed from its original version.

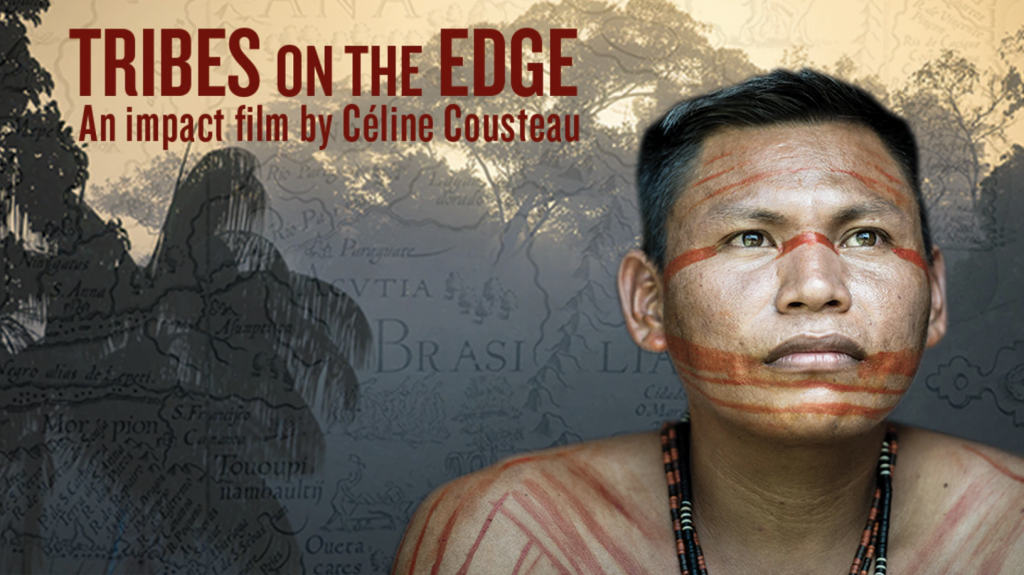

Beto Borges: Thank you for being here, Céline. You’ve recently created a film, Tribes on the Edge, about the struggles of indigenous peoples in the Javari Valley, Brazil, and you’ve founded the Javari Project, an impact campaign born of the film. I think both you and the Javari Project have a beautiful story that people feel drawn to. Could you tell us how your journey with filming Tribes on the Edge started?

Céline Cousteau: The Javari territory in Brazil is the second largest in the country, about the size of Austria or Portugal. As far as I know, there are six contacted tribes. There are also the largest number of uncontacted peoples in the entire Amazon living in this region. Which makes them very vulnerable to outsiders. And this is a region that has been declared irreplaceable in terms of biodiversity by the IUCN.

I first went to the Javari in 2007. That’s when I met Beto Marubo of the Marubo people. He is the reason I created the film. In 2010, Beto [Marubo] wrote me an email asking me to tell their story, telling me they trusted me with it.

So I returned to the Javari in 2013 to begin filming. Tribes on the Edge has become much bigger than I ever thought it would. Back then, I imagined it would be an 8 to 10-minute film. It’s now a 78-minute film and we’ve done numerous grassroots screenings with a big focus on educational outreach. I really believe in order to do some good, I have to honor my promise to them to tell their story, and I’ve chosen to do more. Thus, the film has become a catalyst for the Javari Project.

Beto Borges: What’s the situation there now? What is threatening the people of the Javari?

Céline Cousteau: The threats are very much like the ones elsewhere in the Amazon: illegal deforestation, illegal gold mining, which pollutes the rivers, natural resource depletion, illegal fishing and hunting. There are aggressive interactions between illegal trespassers and the indigenous peoples themselves.

On top of that, there is an administration in Brazil that’s not very friendly towards indigenous rights and the environment. Even though Javari peoples have land that has been designated as their territory, there’s not much defense or support from the government.

It’s also the age-old story of outsiders coming in and bringing their diseases, which is even more evident now with COVID-19. The message I get from them is: we’ve seen this before. And it’s because they saw malaria come in, tuberculosis, hepatitis.

The less obvious threat to people in the Javari is that when some indigenous people leave the territory, they don’t really have a good support system. There are not a lot of resources and opportunities available to them. So they go to the border town of Atalaia do Norte, which is a challenging place, to say the least, and unfortunately, some of them fall into illegal activities as sources of income because there is no alternative. This is detrimental to their own land. If provided with other options and solutions for economic self-determination, they would be more ready for alternatives.

Beto Borges: Tell us a little more about this role you have adopted as you tell the story of the Marubo and other peoples of the Javari.

Céline Cousteau: At the Javari Project, we’re not saying that we think the future of the Javari should look a certain way – we want to help its people preserve their cultures and achieve the future they’re looking to build. I don’t come from there [the Amazon], I won’t live there. I won’t pretend to be anything except a very steadfast ally. And that has been something that, in recent years, I have grown to understand.

It’s been a journey to feel confident about what my role is and what it means, being vocal. Saying, “I don’t suffer the same things that they do, but I stand with them to defend and protect [their lives and homeland].” And where they cannot be, if I have a stage, I will be as a link or as a bridge for their voices. They already have strong voices. Society at large is just not listening.

Beto Borges: What has stood out in the process of becoming a true ally? How do you develop a reciprocal partnership with local and indigenous peoples instead of bringing in your own agendas and hopes?

Céline Cousteau: The type of ally I have become is one who is constantly checking my reason for doing this work. It is always on my mind that I am part of this network for them. A main part of our partnership is about listening and asking. Sometimes it’s difficult, even with the best of intentions.

That’s part of the reason I have to ask myself, “What am I getting out of this? Am I motivated by ego in any way, or is my motivation for them?” Regardless of what the answer is, I think that it’s important to understand this and ask yourself these hard questions.

That’s part of the reason I have to ask myself, “What am I getting out of this? Am I motivated by ego in any way, or is my motivation for them?” Regardless of what the answer is, I think that it’s important to understand this and ask yourself these hard questions.

Beto Marubo is the one that teaches me to calm down when I’m too anxious about what’s happening to them. He’s become like my little brother. I call him, and I say, “Do you need protective gear? Do you need this or that? Can I do more?”

And he says, “Céline, calma. This problem didn’t happen overnight. You by yourself are not going to solve it overnight. You’re here for a marathon, so take your time.” He helps me remember where my place is in all of this. Change is going to take a really long time, and we need to pace ourselves.

Beto Borges: We connected earlier this year and have discussed the future of the Javari Project and an evolving partnership between your team and Forest Trends’ Communities and Territorial Governance Initiative. It would be great to hear your thoughts on what we are building together.

Céline Cousteau: We have come to understand that helping bring economic value to the Javari through the people that are there will be one of the ways to support their cause and contribute to conserve their forest homelands. One of the best ways to do that is to help people in the Javari strengthen sovereignty over their territories.

That’s why we came to Forest Trends, to learn about territorial governance and how to have the right conversations that will lead to actionable plans for indigenous communities.

Partnerships are essential to us getting this work done. To me, the authenticity with which people do what they do is more important than the resources they might have. Much like my team and I have built trust and credibility with people in the Javari, investors, and other collaborators, we recognized that Forest Trends has done the same where it works and has the expertise we need in a partner on the Javari Project.

Beto Borges: Knowing where to begin is a huge challenge in many ways, when indigenous peoples are facing so many threats at once.

Forest Trends has developed a capacity building program on what we call territorial governance (PFGTI in Spanish). It connects indigenous participants with key stakeholders, brings together indigenous groups, and helps them develop a life or vision plan over a yearlong process to give everyone involved more clarity about what is needed for them to meet their self-determined goals.

We have to trust that process, because, like you and Beto Marubo say, this is a marathon. If we want to help support lasting change that helps people and the environment long term, we need to be thinking about both urgent needs and the long view. The Javari is an amazing example of a place with so much richness: the people, their cultures, the forests they have been protecting for centuries.

Céline Cousteau: The fact that your territorial governance process is replicable resonates with me a lot. I love the notion of “open source” in the tech world and I feel that’s what we should be doing as cause–focused organizations and people. If we figure something out, we owe it to all causes and peoples to give it away. It’s a real issue I have with our sector: we’re all looking for resources and end up competing against each other sometimes. And that for me, is a real source of sorrow, even though I understand it.

Beto Borges: In the case of the Javari, hopefully the territorial governance program can be a catalyst for the other changes that need to happen: more direct support from government agencies, healthcare, ensuring their rights are in place, promoting food security over time. People often think that developing economic alternatives is the cure-all. That’s important, but it’s not the silver bullet that will drive conservation and indigenous peoples’ livelihoods.

I see our partnership as a chance to demonstrate how efforts like this can work. How reciprocity and respect and the long-term view look on the ground.

Céline Cousteau: I agree, the Javari is a place of incredible potential. And I like how you speak of the life plan being a process, because you can’t just show up to do a workshop, then disappear. Everything is connected, including the threats these communities are facing. What I still find amazing about working in the Javari is that there’s no panic button there. In many of these indigenous cultures, there’s always the long view in sight, future generations.

This principle can become such a part of you that there’s no other way of thinking. Work like this touches people’s lives, not just those we’re helping, but the people who are helping us, and that is part of the process, whether it’s “our project” or not.

Beto Borges: An awareness of interconnectedness that is so much needed.

Céline Cousteau: So much needed. It’s a gift – all these moments in my work that have added up to an understanding of the interconnectedness of everything. [When] you know that no one person or place is separate, you see yourself as part of one global community and act from that understanding.

Viewpoints showcases expert analysis and commentary from the Forest Trends team.

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter to follow our latest work.