As the U.S., EU, and Australia implement laws prohibiting the import of illegal wood products, all eyes are on China to see if the world’s largest consumer and processor of timber will play its part. Until the Chinese government adopts binding regulation to stop inflows of illegal wood products (or a due diligence system that importers can easily follow), critics fear that Western countries’ move to embrace legality as the norm will simply move the illicit materials in larger numbers across China’s borders – a process known commonly as “leakage.” But the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international agreement formed in the 1960s to regulate the international wildlife trade, may provide a solution for select rosewood species during its Standing Committee meeting this week in Geneva.

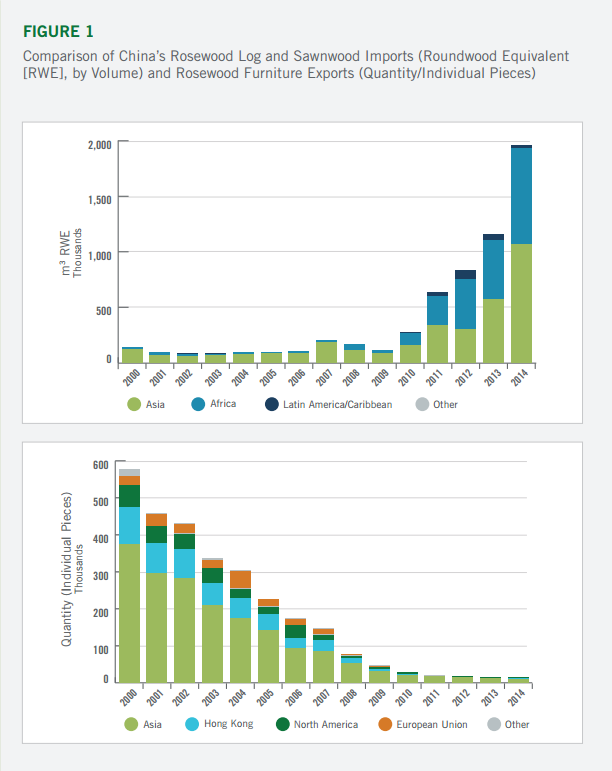

Consumer preference for wood products in China coincides with a cultural shift back to a classical décor aesthetic, first popularized in the Ming and Qing dynasty eras but not seen since the Communist takeover. Demand for luxury furniture made of rosewood, or hongmu (a subset of tree species known for their deep-red hues) has soared among China’s burgeoning middle class at an unprecedented rate, particularly since 2010. A Forest Trends survey of consumer purchasing preferences in 2015 revealed that almost half of respondents had either purchased or were considering purchasing rosewood products, citing their physical attributes, cultural importance, and scarcity as desirable factors.

Editor’s note: Figures and graphics in this piece are excerpted from Basik Treanor’s new report, China’s Hongmu Consumption Boom: Analysis of the Chinese Rosewood Trade and Links to Illegal Activity in Tropical Forested Countries.

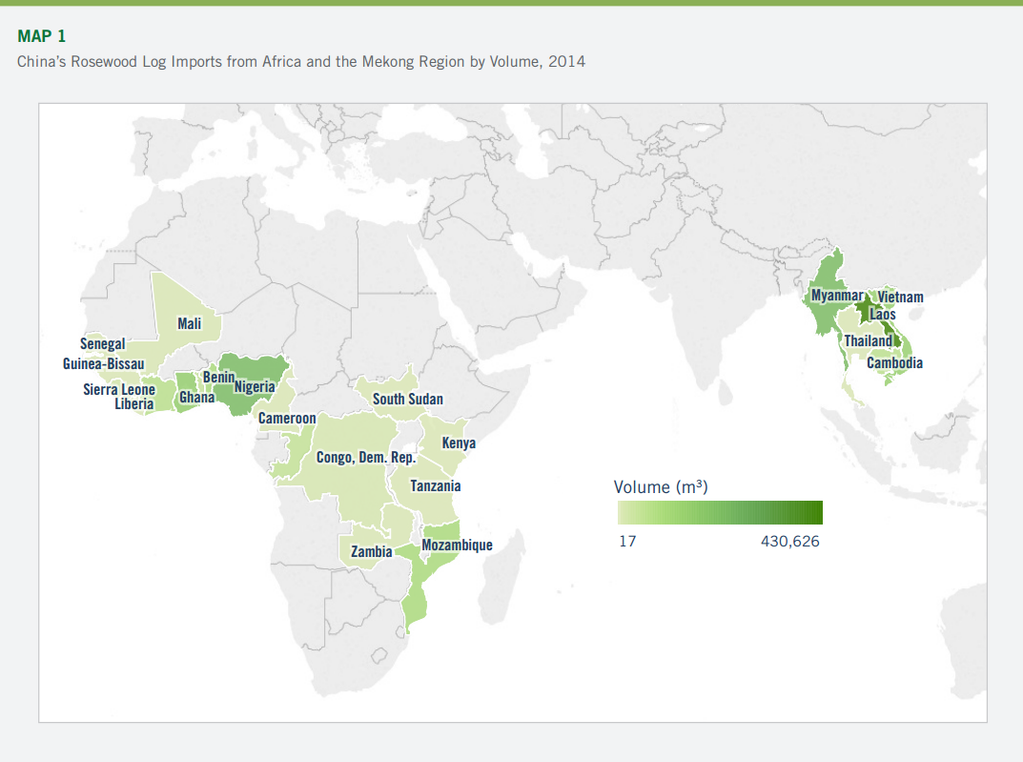

The reemergence of hongmu as a symbol of economic status and cultural importance presents new problems far beyond China’s borders, now that domestic stocks of rosewood are long gone. Rosewood demand is driving illegal and unsustainable logging on an alarming scale in some of the world’s most endangered forests in Southeast Asia and, increasingly, Africa and Latin America. Not only is China the top market for rosewood imports; it’s also by far the biggest consumer – Forest Trends’ data show that more than 99 percent of all rosewood imports stay in the country for processing and eventual consumption.

The international forest community has raised the alarm bells on illegal rosewood for years now. Evidence from Myanmar to Madagascar to Mexico suggests that Chinese consumer demand has not only threatened extinction of the most high-value, in-demand species like Dalbergia cochichinensis (Siamese rosewood), but has also given rise to complex, organized crime networks that facilitate this trade with impunity. Its effects are also felt in surrounding local and indigenous forest communities, many of whom rely on rosewood for fuel, medicine, and income even as they’re coerced by traders to harvest and transport the logs.

Chinese officials, who have codified 33 species of hongmu on a National Standard both for quality control and to encourage industry expansion, place the blame squarely on producer countries. If Laos, Nigeria, Myanmar, and Ghana – China’s top four suppliers of rosewood in 2014 – had better laws on the books and could enforce them, they say, the sector would be transformed. But in reality, almost all rosewood-producing countries do regulate rosewood, at least on paper; most ban harvesting and/or export of logs altogether and strictly prohibit trade in threatened species.

Enter CITES. In the absence of demand-side policy in China – or in Vietnam, a major transit hub for valuable Southeast Asian rosewood – and supply-side enforcement in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, protection under the Convention is seen by many as an immediate, effective workaround. Once a species is “listed,” it’s subject to a licensing system, with permits required upon import, export, and re-export according to a pre-determined degree of protection. China has been Party to the Convention for years, as has Vietnam; both countries respect and enforce requirements. Hong Kong, through which high-risk rosewood shipments had long been routed after China ramped up its CITES enforcement, enacted CITES in November 2014 and made a high-profile arrest this past February.

Political will within producer countries – with technical assistance from NGOs – has spurred a call to action on additional species. CITES listed Siamese Rosewood on Appendix II in 2013, in large part due to Thai leadership, and Guatemala and Belize proposed two Dalbergia species that same year. This week, the CITES Secretariat will consider a proposal from Senegal to list Pterocarpus erinaceus (endemic to West and Central Africa, where rosewood exports to China have skyrocketed 700 percent since 2010), and from Mexico for a genus-wide Dalbergia listing. Both countries have already made considerable progress in increasing inter-governmental awareness of the scale and urgency of trade in these species, and their efforts should be applauded.

Of course, CITES isn’t perfect. Critics have long argued that once it comes into force, suppliers simply shift to “replacement” or look-alike species, and supply chains are easily transferred. In a briefing released on Monday at the Standing Committee, EIA calls for protection of all major look-alike species (including Pterocarpus macrocarpus, which together with Pterocarpus erinaceus comprises 80 percent of the global rosewood trade) and “up-listing” of other species when regulatory measures to control trade are inefficient.

And a CITES listing is no match for effective, enforceable legislation. Many forest-producing countries are negotiating Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs) under the EU’s Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Program, which involve sweeping overhauls of how to define legal trade – a far more in-depth approach than merely requiring exporters to prove whether a product was purchased or harvested legally. If the FLEGT process goes as planned, the need for CITES as a stopgap measure will be far less urgent for producer countries.

In the meantime, protection under CITES remains the most effective solution for curbing the illegal rosewood trade. For that reason, we urge member states to view these proposed protections as an important milestone on the path to permanent solutions and to support them accordingly.

Viewpoints showcases expert analysis and commentary from the Forest Trends team.

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter to follow our latest work.