A report published today by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) alleges that European companies are continuing to skirt import rules and have sourced $1 million of Myanmar teak covertly, despite enforcement authorities and the European Commission concluding in 2018 that such imports cannot comply with the requirements laid down by the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) to prevent illegal timber from entering EU markets. [1]

As long as this common enforcement position stands, importers should refrain from placing teak from Myanmar on the European market. Yet while many European countries have responded responsibly to the common enforcement position, investigating and halting imports of this “non-compliant” timber, the EIA investigation identifies six European companies still importing Myanmar teak into the EU by buying from a Croatian importer in an attempt to circumvent EU law.

The European picture

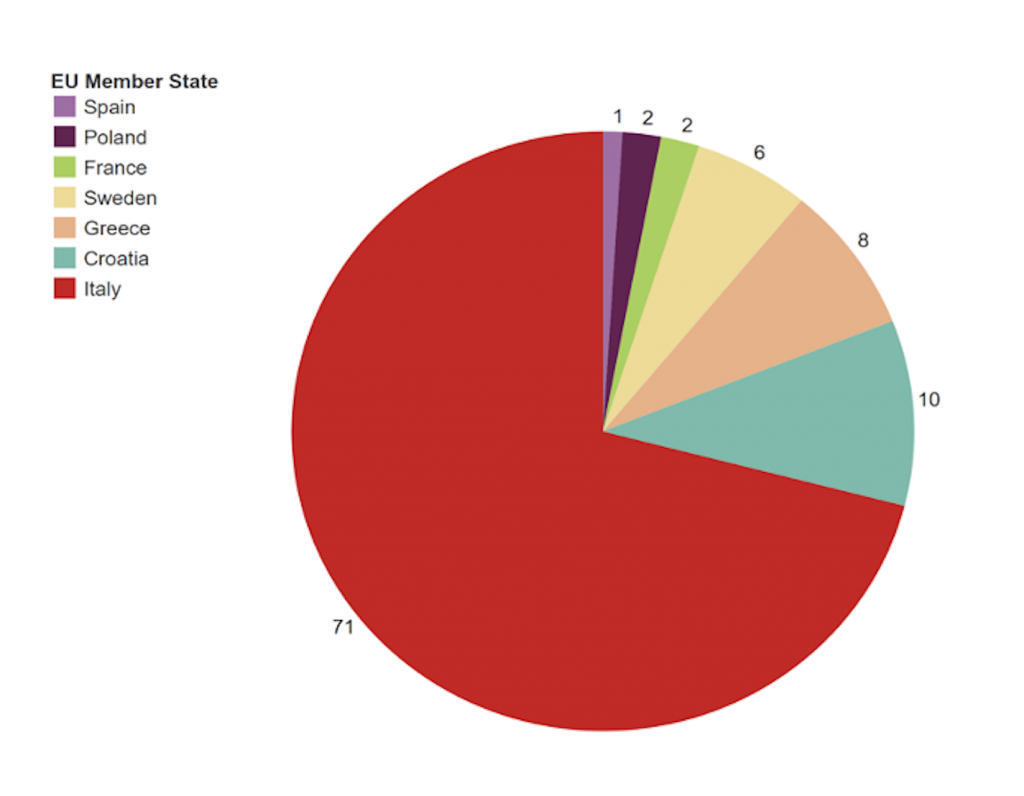

Forest Trends analysis shows that, as of February 2020, Croatia has indeed emerged as the second most significant entry point for Myanmar teak into Europe, and is responsible for 10 percent of all imports in the first two months of this year. The most significant entry point, however, remains Italy, which has been responsible for a vast 71 percent of all European imports in 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of direct imports from Myanmar in January/February 2020 by the main importing EU Member States (based on reported volume in kilograms (kg)). Source: Eurostat Comext, 2020

In March, we released a report examining EU Member State enforcement of the common position. Our data analysis showed that Italian imports have increased annually since 2015, reaching a new high – four million kilograms (kg), worth a total €25.1 million in 2019.

Indeed, trade data indicates that there was as much Myanmar timber imported into Europe in 2019 as in 2017. The only change has been the ports of entry.

Our March paper was based on data reported as of the end of 2019. Since then, another 1.4 million kg of non-compliant timber has entered the EU according to Eurostat in the first two months of 2020, representing a 56 percent increase in imports compared to the same period in 2019.

New entry points and the rise in circumvention

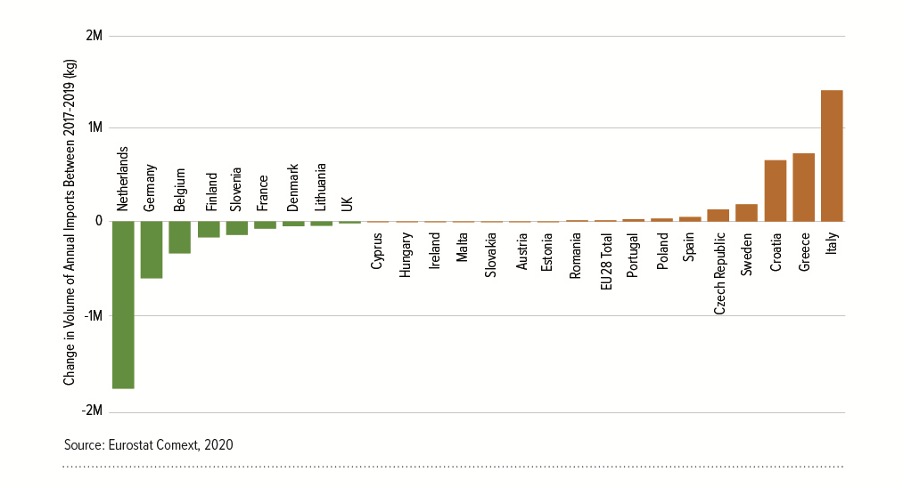

Our data analysis shows that imports of this non-compliant timber are shifting away from countries enforcing effectively, reflecting the inconsistent approach to enforcement of the common position across EU Member States.

Between 2018 and 2019, the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Finland, Slovenia, Denmark, and the UK all reduced the annual volumes of timber imported into their markets from Myanmar, compared to 2017 levels. German, Belgian, and Dutch imports dropped particularly dramatically after strong enforcement activity in the Summer of 2018, which has essentially wiped out direct imports of teak sawnwood and veneer ever since.

In the same timeframe, however, imports rose significantly in five EU Member States: Sweden, the Czech Republic, Italy, Croatia, and Greece (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Change in the volume of annual timber imports by EU Member State between 2017 and 2019

By tracking this high-risk timber, we found that a significant proportion was traded internally within Europe, ending up in countries that have closed off direct imports from Myanmar. In 2019 alone, we identified that more than 3 million kg of sawnwood, valued at over 20 million Euros, was traded to companies based in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Analysis of 2019 trade data further reveals that Croatia, the Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, and to a lesser extent, Sweden emerged as high-risk entry points for companies attempting to circumvent EUTR enforcement to bring non-compliant timber into Europe in 2019. Strong enforcement actions in the Czech Republic closed off the trade, and with the EIA report now revealing Croatia’s action against the importer, this leaves only a handful of countries still importing teak from Myanmar.

If they wish to avoid unfair competition among EU Member States, authorities in Europe must improve tracking of this internal trade to better understand where high-risk entry points for potential circumvention are emerging. However, even where evidence is strong, enforcement officials have limited powers to act. The EUTR only provides significant powers to enforcement officials in those countries where the timber is first placed onto the European Single Market. This means that officials in countries to which non-compliant timber is subsequently transported have little power to act under the EUTR. Instead, some are beginning to use powers designed to prosecute serious organized crime to tackle circumvention of this sort.

A case study in effective joint enforcement

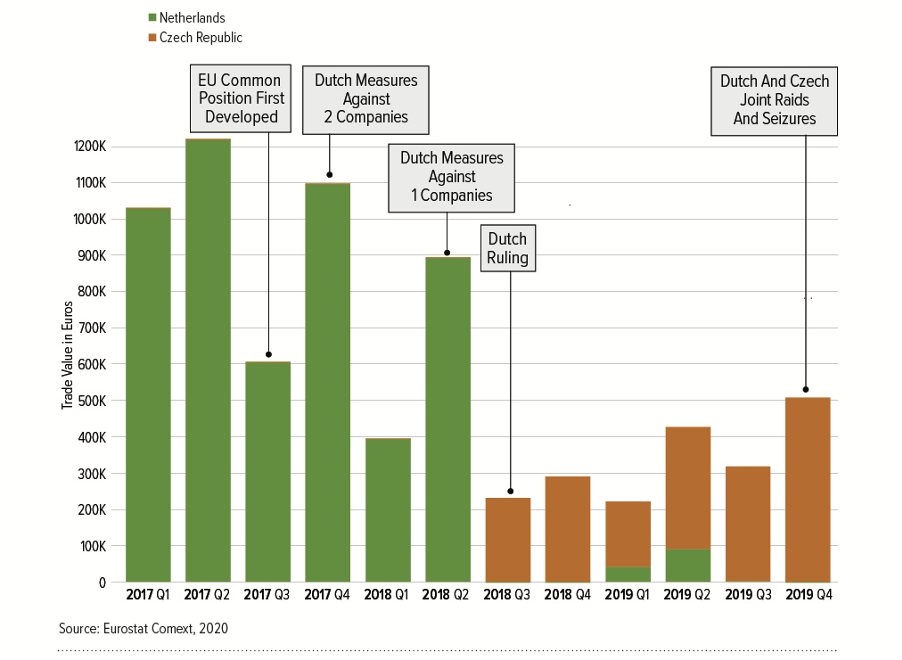

In March, we showed how trade data can reveal specific cases of circumvention (Figure 3). Committed enforcement against Dutch companies led to the Czech Republic emerging as a new entry point into the EU in late 2018 and 2019. Publicly available information suggests that this teak was pre-sold to buyers in the Netherlands. Criminal and administrative cases are currently ongoing in both countries. Imports into the Czech Republic have subsequently tailed off and another entry point into Europe has been closed.

Figure 3: Enforcement actions and the circumvention of timber imports from Myanmar into the Netherlands

Next steps

In light of this new evidence demonstrating inconsistent enforcement of European law across Member States, and a rise in companies deliberately exploiting existing loopholes to their advantage, we believe it is time to:

- Reform the EUTR to boost the power of enforcement officials to investigate and act against traders or seize products further down the supply chain. Making supply chains subject to enforcement in both the country where the timber was first placed onto the Single Market and all EU Member States where the timber is subsequently traded would level the playing field and close this loophole for companies deliberately attempting to circumvent the law.

- Prosecute companies found to be deliberately circumventing EU law with penalties that serve as a genuine deterrent by using powers and sanctions designed to tackle serious organized crime.

- Learn from the existing loopholes and apply the lessons to other EU supply chain legislation. For example, there are mooted plans to regulate the import of forest-risk commodities such as cocoa, palm-oil, beef, and soy to ensure that the conditions for circumvention and unfair competition are not recreated.

Enforcement of the common position on teak from Myanmar is ultimately a test case highlighting the lengths to which companies will go to skirt an EU law designed to protect the European market and European consumers from unwittingly purchasing illegal wood. In this case, all timber imported is non-compliant and therefore easy to trace. In most others, it is much harder to discern legal from illegal through publicly available data. It is, however, reasonable to assume that similar attempts are being made to exploit these loopholes to bring illegal timber into Europe from other source countries and, as such, it is vital that we reform the law to close them.

[1] In September 2017, European enforcement authorities and the European Commission (EC) began developing a joint position on Myanmar teak, concluding in 2018 that such imports could not comply with the requirements of the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR).

Viewpoints showcases expert analysis and commentary from the Forest Trends team.

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter to follow our latest work.