It’s Infrastructure Week in the United States. Communities across the country are discussing how to #BuildForTomorrow by restoring and improving the nation’s infrastructure.

Our water system is broadly supported by two types of infrastructure: the “gray infrastructure” of pipes, pumps, and treatment facilities – and the “green infrastructure” of our forests, grasslands, wetlands, and natural waterways.

Both are under threat, but only one is getting anywhere near the attention it deserves.

America’s aging gray drinking water infrastructure continues to be in drastic need of replacement, repair, and upgrading – receiving a D in the latest American Society of Civil Engineers’ Report Card. The Flint water crisis – which is still impacting people – is the most dramatic example of the consequences of outdated infrastructure in combination with the (at times criminal) failure of institutions to manage the public trust. Damage from storms and flooding – from Hurricanes Katrina to Sandy to Michael – has disrupted water supplies for millions of Americans over the past 15 years.

But while our gray infrastructure gets a D, no one is even bothering to grade our green infrastructure. We do know, however, that the picture isn’t good.

We know, for example, that the United States lost about 89 million acres of forest from the beginning of 2000 through the end of 2017, and that the bulk of this loss is in the south, where 21 million people – about the population of Florida – receive their drinking water from national forest lands.

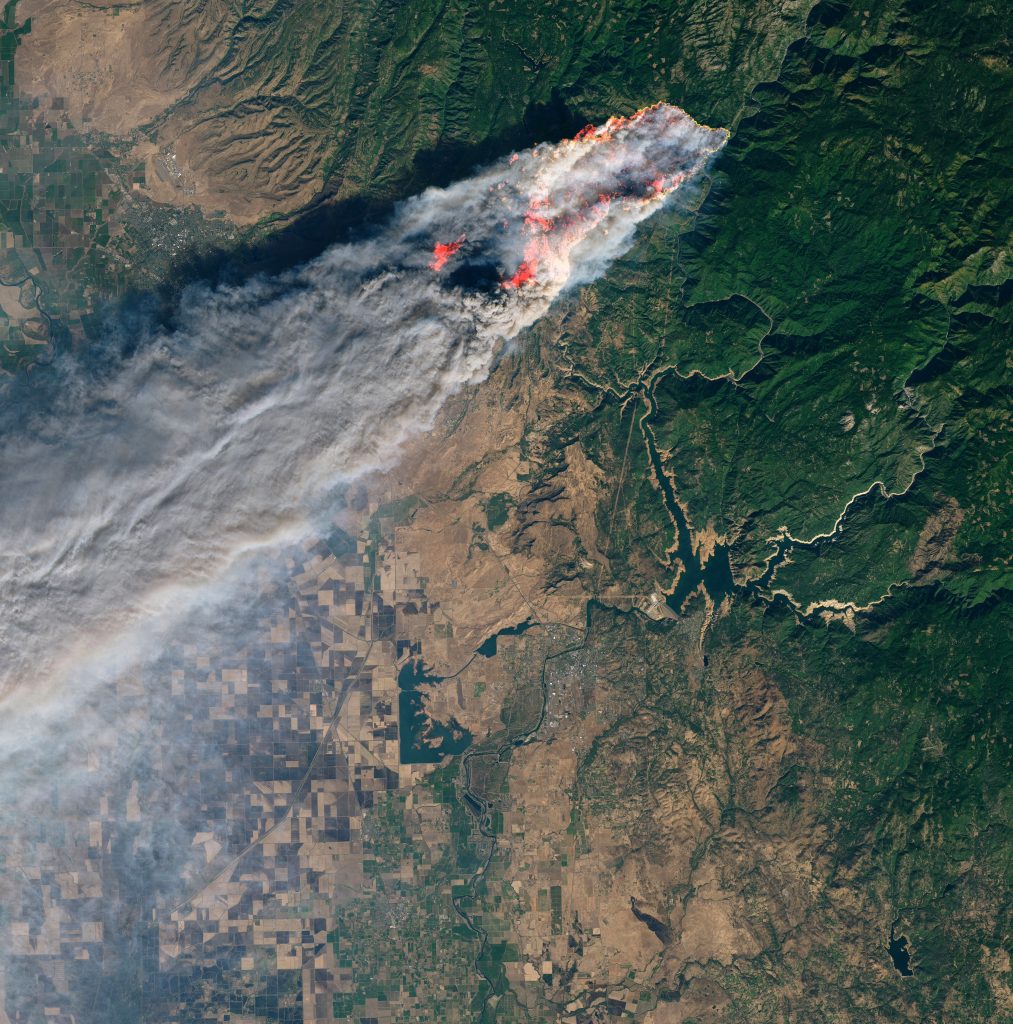

We also have evidence of the dire consequences to water supplies when forests are lost through wildfires. Over the past several decades, increasingly severe wildfires from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast have cost lives and billions of dollars in property damage.

Wildfires significantly disrupt water supplies. They cost utilities and ratepayers hundreds of millions to repair damaged infrastructure, dredge reservoirs, and purchase water from alternative sources. A recent review of just four wildfires in Colorado, Montana, and California found over $120 million in costs borne by water utilities. This doesn’t include the costs to federal and state agencies and local communities for fire suppression, and damage to property, transportation and energy infrastructure.

If these flashing lights are not enough, the most recent and sobering climate assessment by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows that with current trends we will see 1.5 degrees C global warming in as little as 12 years, bringing more frequent and deeper droughts, and thus more frequent and more damaging wildfires.

An Infrastructure Deal for the 21st Century

President Donald Trump and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi recently reached across the political divide to agree to spend up to $2 trillion to fix America’s battered infrastructure.

That infrastructure deal has yet to be constructed. But it should include investments in green infrastructure – not just gray.

First, green infrastructure reduces risks to gray water infrastructure from hazards such as flooding and wildfire. It improves the performance and reduces the costs of operating gray infrastructure when the two are integrated. In some cases, green infrastructure can even be a more cost-effective alternative than gray.

Secondly, both urban and rural communities benefit from green infrastructure. The restoration economy is a $25 billion-a-year industry that supports more jobs than coal, logging, or iron and steel. These are jobs that can’t be outsourced, and are often located in small towns and rural areas. In cities, green spaces are associated with improved health and lower crime rates.

Finally, we can meet both our water and climate challenges by approaching them as one interconnected crisis. Because water and climate are so intimately linked, getting to 1.5 degrees, not to mention going beyond, will greatly increase the risk to water supplies in the US.

The new IPCC report starkly clarifies that there are no pathways to staying below 1.5 degrees C warming that do not entail the active removal of greenhouse gasses already in the atmosphere. In other words, we don’t just need lower emissions – we need negative emissions. The good news is we have nature’s original carbon technology ready at hand, in the form of better management of our forests, farms and fields. “Natural climate solutions” can deliver 37 percent of the mitigation needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s 2-degree target. The coalition behind the Green New Deal says it’s focusing on land-use as a core strategy to reduce emissions and pollution.

These solutions dovetail with green infrastructure approaches to water security. A single investment in the landscape can provide clean and reliable supplies of water, while actively removing carbon and nitrogen from the atmosphere and storing it in trees and soils.

Investments in green infrastructure aren’t new. In 2016, California legally recognized meadows and streams as part of its infrastructure.

An investment approach to green infrastructure can also attract bipartisan buy-in. A recent policy memo issued by the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Water declared strong support for water quality trading, which creates incentives for farmers, foresters, and landowners to manage their lands to improve water quality. The memo is part of the administration’s broader efforts to “accelerate investments in infrastructure and technology that will improve America’s water quality.”

An Asset Management Approach

And importantly, we need to recognize our green infrastructure for what it is – assets that are just as valuable as our dams and treatment plants. Individual water utilities, cities, states, and the nation need to fully consider natural assets in the mix as we address our infrastructure challenge.

A first step would be to create local to national report cards for green infrastructure – similar to the ASCE’s gray infrastructure report cards – to inventory natural assets, assess their condition or health, and identify the benefits they provide.

Next, utilities, cities, states, and the nation should embrace natural asset management. In the same way that well-managed utilities strategically assess their gray assets, we can evaluate our green infrastructure base: how much assets cost, the value they provide, what maintenance is needed, how long assets will function before needing replacement, and how to minimize risks.

We’ve seen the dismal results of continually deferring maintenance of our gray infrastructure. As we roll up our sleeves on new infrastructure investments, it’s time to design smarter 21st century hybrid systems that deliver for us on water security, jobs, climate resilience, and healthier communities.

Viewpoints showcases expert analysis and commentary from the Forest Trends team.

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter to follow our latest work.