Cambodia is losing its natural forests at a rate of about 208,000 hectares (804 square miles) a year, according to a new report from Forest Trends. The primary culprit? Land concessions granted by the government, which are intended for large-scale commercial agricultural crops and supposedly mainly on degraded lands, but are instead being used solely to clear-cut large areas of Cambodia’s oldest and most valuable remaining forests – some of the most biodiverse in Southeast Asia. These economic land concessions (ELCs) are now often being used as a vehicle to circumvent national laws in order to profit from the clearance of timber, with or without ultimate intentions to deliver on agricultural development commitments. Thus, many ELCs are operating almost as de facto logging concessions, despite the fact that Cambodia officially ended those in 2001.

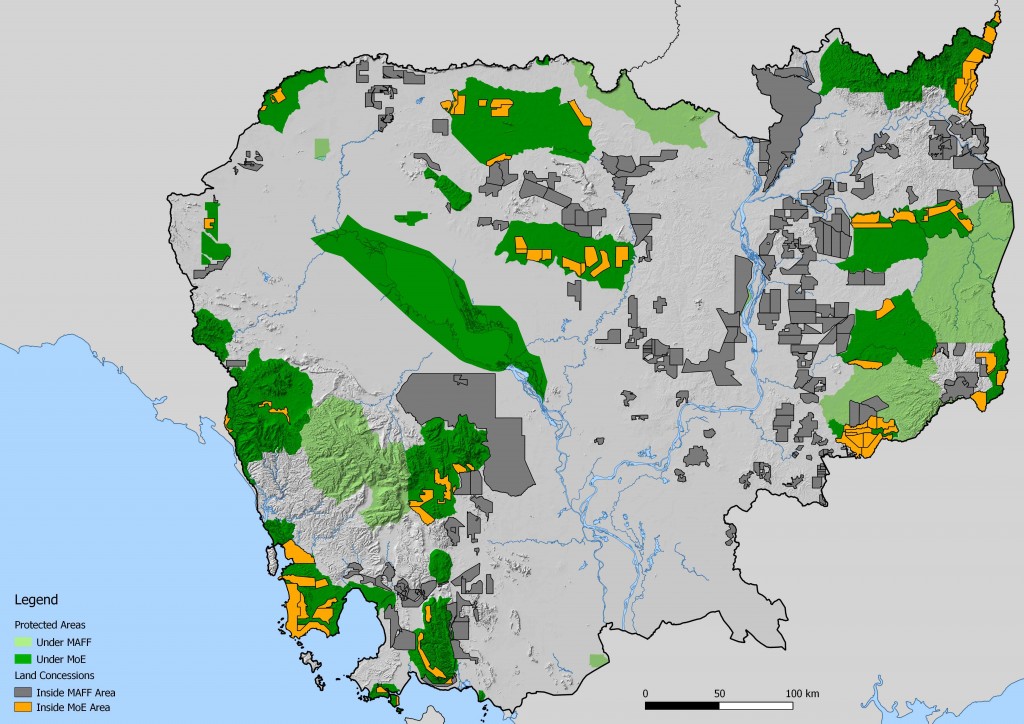

A recent Forest Trends report on illegal deforestation and production of illegal conversion timber in countries throughout the Mekong, entitled “Conversion Timber, Forest Monitoring, and Land-Use Governance in Cambodia,” shows that in 2013 the extent of these ELCs reached 2.6 million hectares, almost four times the amount in 2004. By the end of that year, nearly 14 percent of the country had been allocated to domestic and foreign corporations for large-scale agriculture and other development; of that, 80 percent was within protected areas and national parks.

Using satellite imagery and forest fire data collected by NASA for Cambodia during the 2012-13 dry season, Forest Trends researchers demonstrated that carbon emissions from evergreen forests cut inside ELCs were almost 10 times higher than those outside the agricultural concessions, confirming that corporations are targeting the oldest and most valuable forests. In particular, the extent of valuable, dense evergreen forest is disproportionately high in concessions located within protected areas. This directly contradicts the government’s claim that ELCs are being allocated on degraded lands, or in forests not worth conserving or restoring.

Local groups inside Cambodia have for years suspected that the government has allowed companies to use ELCs as if they were logging concessions. ELC leases go for a few dollars per hectare and allow for clear-cutting rather than the sustainable management that might be required under a legitimate selective logging system. One cubic meter of some of the best timber can earn a staggering profit. At those rates, the Cambodia Daily notes in a new long-form feature on the topic, “a prime concession can quickly pay for itself and more.”

The impact of these land concessions on forests extends far beyond the borders of these massive tracts of land. Apart from representing an institutional failure on its own, the ELC system serves as an indictment of other governmental structures geared toward forest conservation, including protected areas designations. The Ministry of Environment (MoE) is responsible for much of the nearly 550,000 hectares of land concessions that are allocated within official protected areas. The very existence of this loophole undermines the purpose of the Law on Protected Areas, which does not provide for the legal development of large-scale plantations, and also Cambodia’s forest and protected area management in general.

The Forest Trends report also underscores that until it develops legitimate and transparent institutions, Cambodia is ill-equipped to participate in international forest sustainability programs like REDD+. Measured against the widespread clear-cutting of Cambodia’s forests, existing REDD+ projects in the country represent little more than a drop in the bucket.

The Cambodian government recently made headlines by taking steps to reduce the duration of ELC permits, from as much as 99 years to 50 years, and announcing the seizure of approximately 90,000 hectares from companies. Even if this signals a new policy, it doesn’t come close to solving the problem. Whether you give someone two weeks to loot a museum, or a month, you’ll likely get the same results. Intervention must take place before the damage is done – not a half century later.

In order to achieve a legal, sustainable timber supply that accommodates sustainable economic development in tandem with forest conservation in Cambodia, much more meaningful action is needed. This should begin with a moratorium on logging and timber transportation in ELCs and social land concessions (SLCs) until minimum requirements for transparency and rule-of-law are established. The government needs to conduct an expedient review of land concessions to determine which developments comply with Cambodia’s existing laws and regulations. Rewarding legitimate agriculture that is practiced within existing laws – and penalizing producers that harvest natural forests under false pretexts – will create a compelling incentive for better land-use planning and, ultimately, sustainable forestry practices.

Viewpoints showcases expert analysis and commentary from the Forest Trends team.

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter to follow our latest work.